Motive

If you’ve worked on a project without an asset registry, you’ve likely come across the following scenario: An asset is used in 6 places and it’s path is hard-coded in all 6. On it’s own, this isn’t that big of a deal. Much like magic numbers, it will never pose a problem until you need to change them. At that point, however, you’ll be stuck desperately trying to find and replace and hoping you don’t cause collateral damage. This problem becomes exponentially more frequent if you have artists on your team. If you do, your asset names will quickly go from frog.png to frog_green.png to frog_green_new.png to frog_green_new_revised_final_last_draft.png. As a result, it becomes necessary that the asset names in your code, are abstracted away from the literal filenames in the OS filesystem.

Design Goals

The AssetRegistry exists to achieve the following system design goals:

- Serve as an added layer of abstraction above file paths

- enable easier asset directory refactors

- enable separated Asset and SaveData

- Provide an OS-agnostic interface

- support for Windows 64, Linux, and Horizon operating systems

- Encourage the use of Packages as a method to store relevant Assets as a collection where they’re used most often

- Encourage the use of Assets as a method to handle how file data is read, saved, and managed within the engine

- Keep files from being reread unnecessarily by storing their data in ram

Abstractions

The following sub-sections are organized in layers of abstraction. I’ll start with the most basic way to manage directories and each additional subsection will extend the functionality until we have a final product that meets all our design goals.

Abstraction Level 1: INI file

In an effort to address design goal 1, we can reference all assets by name and store the dictionary between name and path inside a separate file. This would look something like this:

ini file:

1 | frog_texture = "Assets/Images/Frog/frog_green.png" |

c++ code:

1 | std::unordered_map<std::string, std::string> Assets; |

Pros

- Very easy. Provided you either write a basic ini parser or use an external library, you can have this method working in no time.

- When files are renamed or moved, you only need to modify the ini file

Abstraction Level 2: Assets

Ideally Asset should be a c++ class. This way they can be extended in the future and can have more functionality than simple strings. for now we’ll just make it a glorified std::string that stores the OS file path.

Pros

- If implemented effectively, assets can be modified relatively easily in the future

- starts work towards design goal 4

- starts work towards design goal 5

Abstraction Level 3: Packages

to address design goal 3, let’s create an object - call it Package - that stores a dictionary of assets. this way users can organize their assets in a meaningful way.

in order to achieve this, we need to reflect the concept of packages in the ini file. For this we can use section headers:

1 | [Textures] |

Pros

- If implemented effectively, packages can be modified relatively easily in the future

- names can be reused across packages.

- package names can give hints to their content’s type so names like

frog_texturecan be reduced tofrogin the packagetextures

Abstraction Level 4: Asset Registry System

If you were to implement all of the above abstractions with no changes, you’d end up with a Package class, an Asset class, and no where to store their instances. Abstraction Level 1 proposed the use of an unordered_map, but making this public and global would be unwise. There’d be no way to control how it’s used and no way to switch it out with a different data structure. This abstraction level implements an Asset Registry namespace or singleton that provides the following interface.

1 | void LoadRegistry(); |

Pros

- If implemented effectively, the back end can be modified relatively easily in the future

- the interface gives hints to the user how it’s meant to be used reducing the need for excessive documentation

- any OS specific operations can be performed privately and the interface is maintained across the board. This fully meets design goal 2

Additional Features

Now that we’ve built a full abstraction model, let’s try to address some of the remaining issues by adding more features

Additional Feature 1: sub-packages

If you simply make packages capable of also storing references to other packages, they can act very similar to symbolic directories. Here’s how that might look in the INI

1 | [ClassicMode] |

Using a flat format like this allows multiple packages to reference the same sub-package without having duplicate data. That way you can organize the data in multiple ways at the same time and use the organization that works best for the use case

Note: this is no longer a syntactically correct ini file because it uses both ‘:’ and ‘=’. The library I’m using allows this but you may need to represent your data differently if you’re using a different ini parser

Additional Feature 2: Asset and Package inheritance

A big limitation we still have in the proposed system is that assets are still just file paths and there’s no way to extend them to de-serialize the data properly and provide relevant methods. for example, an exe asset would ideally have a “Execute” method and a sprite asset would ideally store it’s render data in ram after it’s loaded. Thankfully c++ provides us with inheritance to solve this. We simply need to make our getters templates that cast to the requested type:

1 | template<typename PackageType = Package> |

For the DeltaBlade engine, we decided that real time type reflection was overkill so the assets are all stored internally as std::shared_ptr<Asset>s and are simply replaced with the extended type when GetAsset is called. With proper runtime type reflection however, you could choose to serialize the type inside the ini file and then load the correct type at startup. This would allow for assets to be preloaded easier without having to know the type externally.

Additional Feature 3: Registry Paths

The Asset Registry introduces a concept known as Registry Paths. Similar to filesystem paths, this is a way to represent a series of packages, and sub-packages opened in order to retrieve an asset as a colon delineated string. if for example, your AssetRegistry.ini file looks something like this:

1 | [UI] |

then retrieving the menu music could be done in any of the following ways:

1 | // opening packages individually |

1 | // using registry paths |

1 | // using a hybrid |

This feature is purely syntactical but it speeds up development significantly and keeps packages from being a burden to use

Post Mortem

While the registry paths were great in theory, they ended up encouraging an unfortunate coding style in practice. Users would end up creating interfaces that took a single string representing the entire registry path - not too different than a file path. As a result, the registry had to do far more map lookups than necessary and didn’t pass around packages like they were intended. If I were to redesign this, I might remove this feature entirely unfortunately.

Additional Feature 4: Editor

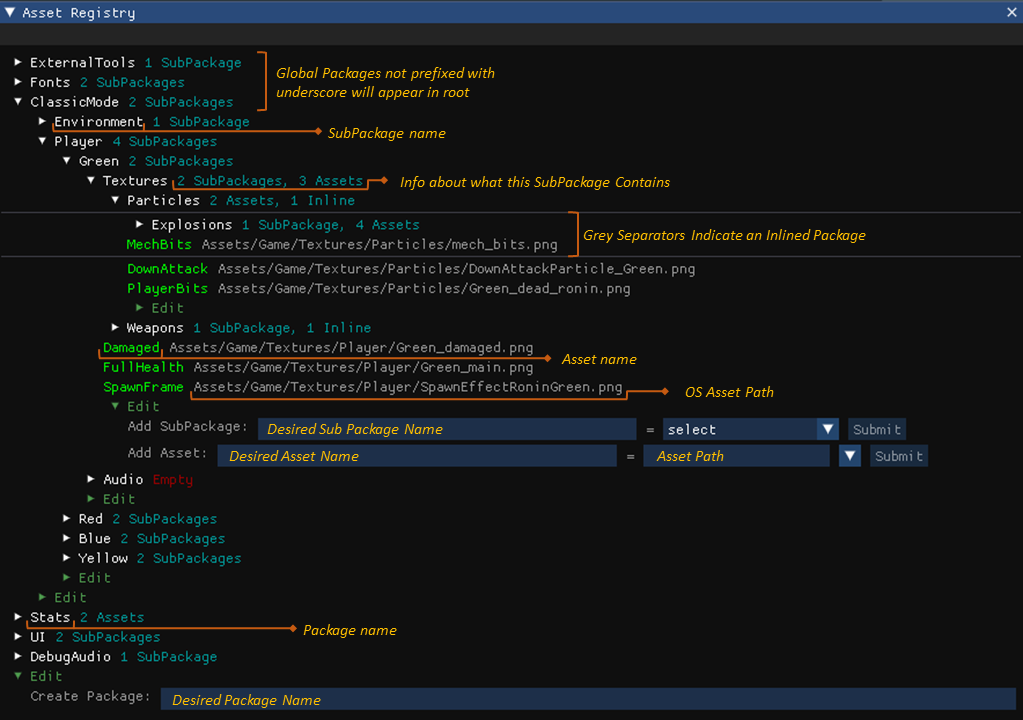

You’ve officially made it to the fun part. This is where the pretty pictures and gifs live! When developing the registry it became quickly apparent that the ini was going to blow up and become increasingly difficult to parse. To solve this, I wanted to allow users to modify it in a better environment than a text editor. Using ImGui I made the following tree based editor

As you can see, when changes are made in the editor, they’re saved to the ini in real time.

The editor supports

- viewing the contents of packages

- adding packages, sub-packages, or assets

- removing packages, sub-packages or assets

- copying the OS path of assets to the clipboard

- copying the registry path of assets and packages to the clipboard

- copying the name of assets and packages to the clipboard

Additional Feature 5: Error Handling Modals

I could’ve called this project complete at this point. I’d met all the design goals, made a great editor, and provided several ways to access, read, and modify the data. What’s important to remember however, is that I’m implementing this for humans. And humans are known for two things:

- They’re lazy. They don’t want to use a system if it’s not stupid easy

- They’re prone to mistakes. Even if they know not to rename files without modifying the ini, they’re probably going to forget at some point.

all decent systems have some form of error logging but all great systems can completely resolve the errors without crashing. I’m of course striving for greatness. Let’s consider the worst case scenario:

A user renames a core file such as a default shader from ‘Assets/Game/Shaders/forwardVert.glsl’ to ‘Assets/Game/Shaders/forwardVert_Renamed.glsl’ and forgets to modify the ini

With the proposed system, the game would crash immediately. The best we could do is return nullptr or throw an exception and hope it’s caught but realistically, what could the renderer possibly do? It can’t render anything without a shader and there’s no way for the renderer to find it.

Instead, I have the registry ask the user and wait for their response. To do this, I had to create a completely separate application and launch it from the editor when there’s a problem. This application simply walks the user through fixing their error and quietly resumes as if nothing happened

The following errors are handled in this way:

- A package was requested in code, but it’s not in the AssetRegistry

- An Asset was requested in code but it’s not in the AssetRegistry

- A sub-package was requested in code, but it’s not in the AssetRegistry

- An Asset was renamed but the ini wasn’t modified to reflect the edit

- An Asset was moved but the ini wasn’t modified to reflect the edit

This feature becomes particularly powerful when you stop thinking of it as error handling, and instead think of it as a part of the pipeline. The previous pipeline was as follows:

- put file inside Assets directory

- modify ini file (either directly or by launching the editor and modifying it there)

- write code that uses the asset

but this isn’t how most devs like to work. If you’re like me, you’d much rather write the code first. After all, we want packages to reflect how the assets are used and that might not be clear until the code is written. By intentionally expecting an error from the registry though, we can write the code first and let the error handler do the rest:

- put file inside the Assets directory

- write code that uses the asset - making up names for the asset and it’s package(s) on the spot

- launch the editor and get an error that the name doesn’t exist

- link the asset using the modal

- continue testing the game/editor as normal

Additional Feature 6: Hot Loading

One request I routinely the other developers was asset hot-loading. This essentially required two things:

- Implementing a virtual

Reloadmethod in the Asset Class - Subscribe to the OS filesystem events to track when a file is modified and call

Reloadwhen it is

the first step is self explanatory to anyone who understands inheritance, but the second will involve writing OS specific code and wrapping it in an abstraction layer. For windows, I followed this great resource by Jim Beveridge and for Linux I used inotify.

Useful Resources

Simple INI parsing library: mINI

Basic, cross platform ImGui interface that I used for the modals: Hello, Dear ImGui

How Unreal Engine handles assets: docs.unrealengine.com